“Young black girls want to see themselves in the roles to which they aspire. If they can’t see themselves, they’re not going to think they can be it. It’s been a challenge we see over and over again in the tech industry,” says Avis Yates Rivers. “How many prominent women or women of color can you name in the tech industry? Everyone can rattle off Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, etc. Can anyone name any women? Any black women?”

“Young black girls want to see themselves in the roles to which they aspire. If they can’t see themselves, they’re not going to think they can be it. It’s been a challenge we see over and over again in the tech industry,” says Avis Yates Rivers. “How many prominent women or women of color can you name in the tech industry? Everyone can rattle off Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, etc. Can anyone name any women? Any black women?”

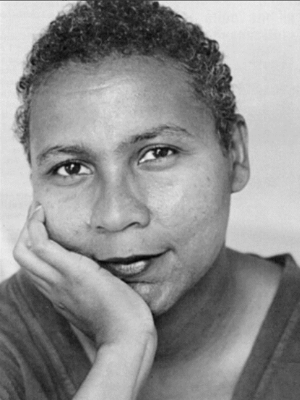

As a Black woman tech founder and CEO powerhouse, Rivers is coming at inclusion in tech with everything she is made of – from authorship to launching an organization for girls and young women in STEM to personal visibility: “As an entrepreneur, you see a problem and you figure out how to be the solution and bring positive results to that problem. So, I’m addressing the problem of the underrepresentation of black women in technology as an entrepreneur would.”

Being a Serial Entrepreneur She-EO

On the business front, Rivers founded her first firm after five years of selling early technology on Wall Street in 1985. After five short years at Exxon Office Systems, she had mastered sales and the ability to ‘manage her business’ as she ascended the ranks at Exxon. After a divestiture of that subsidiary, she decided to continue to support those customers by launching her first company out of her basement. When we talk tech, Rivers was selling the first full screen word processor and first generation of fax machines before PCs were ever in offices or homes.

“Exxon taught me how to sell and that held me in the highest good through my career, because to be successful in business, you have to know how to sell,” says Rivers. “It’s an art – the art of relationship building – and that’s key for being successful in any walk of life. You have to build strong relationships – whether mentors, sponsors, advocates, advisory board members or employees who can embrace your vision.”

Proclaiming herself a “serial entrepreneur” and with a sign reading She-EO propped behind her on Zoom, Avis has founded five tech companies since 1985, Technology Concept Group International (TCGi) and its predecessors, as well as acquired two. What animates Rivers in her business is being able to bring a tremendous amount of awareness, size and value to customers who are looking to transform their procurement practices. TCGi has three pillars of business: procurement solutions, technology solutions and talent management solutions.

“I love to help corporations rethink/reimagine how they spend their money,” says Rivers. “When we take a look at how they’re currently spending, there’s so much opportunity for improvement, for streamlining, for more accurate data capture and for more digital transformation.”

Necessary Inclusion Of Black Women In Technology

“It’s so key that I take an active role in correcting the underrepresentation of black women, specifically and intentionally, in tech,” says Rivers. “I advocate for all women in tech but the numbers for black girls and women continues at the same weak pace and has not grown to my satisfaction.”

In 2017, Rivers published her book Necessary Inclusion: Embracing the Changing Faces of Technology, and since then has been speaking on a global stage: “I wanted to broaden the conversation around what technologists can and should look like, which is anybody and everybody. And not just the image that is portrayed over and over again, in media, film, and entertainment. And to ask what are some of the things that we all can do to support more women in technology?”

She’s also taking a direct role in developing the next generation of diverse tech talent. Her company launched the TCGi Foundation, which is focused on breaking down barriers and creating opportunities for black girls and women in tech through efforts including exposure to hands-on experience, networking help, mentoring and college scholarships: “We help them to stay connected and persist even when it gets hard in college and to help them move into tech careers. TCGi directly hires some interns upon graduation. So, the Foundation is really fulfilling for me. That’s my purpose and passion work.”

To truly diversify the next generation of tech talent, Rivers knows encouragement from an early stage is critical. She was recently thrilled to see her five and three year old grandchildren playing with a coding kit for kindergartners with both black inclusive imagery and messaging. Rivers stresses that if it were easy, everyone would be doing it. It is difficult and being prepared, tech educated and well positioned for internships and career opportunities is essential.

“Being able to encourage, guide and support black girls to realize from a very young age that they are good enough, smart enough and this is something they can do matters entirely. They need to be able to see themselves,” emphasizes Rivers. “If I could do but one thing, it would be this: gathering with them, speaking to them, showing the way and mentoring more girls and young black women into tech. My voice needs to be heard, but my face also needs to be seen.”

Owning Your Ground and ‘Black Girl Magic’

“When I introduce myself, I often say that I’ve been born doubly blessed – black and female,” says Rivers. “I know my early success in selling technology had a lot to do with the fact that I was not a common sight on Wall Street. Then once you opened the door (provided the access), I could do the rest,” she notes. “But I also had to basically ‘steel’ myself physically and emotionally. I was encouraged to knock on every door in my territory and eventually earned the honor of being named Rookie of the Year. It was sheer persistence (and a healthy dose of encouragement from family) that I was able to persevere. I never know how I would be perceived and/or welcomed during those early days. I knew I was being judged before I even opened my mouth. We all are, just based on how we look. But it encouraged me that I had a distinction that set me apart from the white guys on either side of me, and I leveraged that as a benefit.”

Since George Floyd and the salience and acceleration of social justice issues, Rivers feels that black businesses are being recognized more and should own the moment. “So many corporations have stood up and made public commitments that they’re going to spend billions of dollars with black firms. I was like, okay, so we’re in vogue now,” she says. “So, it’s important for people like me to help them fulfill those commitments. It’s a change that has to be encouraged, enabled and managed.’”

She continues: “The longer I’m out here (over 3 decades now), the more unapologetic and forthright I’ve become. I continue to ask for what I want and what I believe I deserve, because I’ve worked hard and have earned the right.”

Rivers also talks frequently about ‘black girl magic’: “The notion of ‘black girl magic’ picks up on this je ne sais quoi, this essence, this flava, this presence, this power that is just now starting to be appreciated and recognized.”

“The reason behind the momentum is because there are more black women ascending into positions of power. We have a handful of black female CEOs, a black Vice President of the United States, and some black female billionaires now. It’s not just Oprah anymore in media and entertainment. The numbers are starting to swell, though still not where they should be,” she notes. “But because we’re extraordinary in those spaces, people take note to see how we show up and speak up. That’s why I feel committed to using my voice and my ‘black girl magic’ on behalf of those who do not have a voice.”

That same commitment goes for voice and her presence: “At this point in my career, I’m just very dogmatic about making sure that we’re treated with respect and included. If someone sends me an invite to a webinar, and I look at the speaker line-up, and I don’t see any black women or men, I immediately let them know that you really don’t want me there. Because there’s no representation. The more voices that insist that representation happens on every level, the faster we’ll get to any kind of equity.”

You Make the Choice to Belong

One of the best pieces of advice Rivers received early on was: you act like you belong. You walk in the room, and you act like you belong.

“I have walked into several rooms where I wasn’t invited, but I acted like I belonged. Then what are they going to do except welcome me?” she says, having even pulled it off at a presidential inaugural ball by bringing an extra guest with her invitation. “You walk into a room, and you act like you belong. Take a seat at the table. Not in a chair along the wall, but at the table. And then raise your voice when you speak so you can be heard.”

She also says it’s important to challenge the people who talk over you, the ‘alpha males’ who speak over other men and women or take credit for others’ ideas: “We have to use our voices to make sure those lines don’t get crossed.”

For her own success, she’s found it critical to be prepared. “You can’t fake it until you make it, especially at the level I’ve reached. I have to come to the table prepared.”

More on Her Back Story: Are Entrepreneurs Made or Born?

“Are entrepreneurs made or born?” Rivers asks, frequently. “The answer is yes: they are both. There is something inside of a true entrepreneur that isn’t easily fulfilled, no matter what role ‘they’ continue to accelerate you into.”

She reflects back to her own leap: “I was on a fast track at Exxon and being promoted every 12-18 months and loved when they moved me into sales. But a voice inside wouldn’t let me rest. I kept quieting that voice down because I’m from very humble beginnings; silver spoons didn’t exist in our house. I’m one of six kids born to two working-class parents growing up in New York City on public transportation and in public school. Although I worked on Wall Street, I wasn’t connected with capital markets,” she says. “So Exxon did me the biggest favor by selling that division out from underneath me. I had only worked for Exxon, including three internships in college, and never anticipated working anywhere else. But when they sold that division, I knew it was my time to take a leap of faith.”

Rivers already had a proven record on Wall Street and knew a fallback was finding another sales job. So, after writing the pros and cons, and excited for the opportunity to manager her clients, schedules and revenue in her own way, she set off on her own – and she brought along the same client install base she’d established from the five years in tech sales for Exxon, because she asked for it.

“It’s confirmation of the old adage: you don’t have because you don’t ask.”

Entrepreneurial Resilience As a Black Woman

From 9/11 to the greatest economic recessions to civil unrest and extreme weather, Rivers has had to face many headwinds and find her way forward.

“It seems like all of my resilience has come from sinking into financial holes and having to climb back out,” tells Rivers. “I was involved in the greatest U.S. corporate bankruptcy of all time (her largest customer filed for bankruptcy protection and she carried them on her own back to complete the project). I climbed back out. I had to deal with the greatest economic recession of all time in 2008. I climbed back out. I had to do it with the terrorist attack on 9/11. I lost 35% of my business that day – no notice, no fault of my own. I climbed back out. Through all of it, I’ve had to keep going, because to me, stopping was not an option.”

The lack of capital going to women and black women-owned businesses puts founders like herself into a financial roulette and great personal risk.

“Companies like mine are undercapitalized, which means we are able to make money and then spend the money that we make, but nobody’s handing us millions of dollars to fuel our growth. During the .com boom, folks that didn’t look like me were getting millions for an idea that they sketched out on a cocktail napkin – no company, no customers, no revenue, no track record,” she explains. “Folks like me who were not connected to that activity had to do the best we could. A lot of times that required going into the hole, suffering a loss, having to let people go, or getting behind on vendor invoice payments, etc. So, it’s been a journey. But resilience? I’ve modeled that in stone.”

Get Support And Know Your Numbers

If Rivers could redo anything differently, she’d say, “Don’t keep going it alone. I’ve been a sole owner my whole life. I would tell myself to find a good partner with complementary skillsets so that you can go farther faster. What is the old adage? If you want to go fast, go alone. But if you want to go far, go with somebody else.”

Had she known then what she knows now, Rivers would have been in the capital markets game. Her biggest growth curve has been her skillset around the finances, which happened after a trust rupture where she lost a lot: “That taught me a valuable lesson – to know my numbers and learn them for myself. I don’t have to be in the nitty-gritty of them, but also nobody has the authority to move money out of the company except me. Now, I have to approve it.”

Going further, she says: “I would say the financial aspect of running and growing a business has caused me to grow. Working with capital markets has caused me to grow. Understanding how the business is valued and what are the different components of the financial statements has really caused me to grow, so, now I have those conversations with private equity people.”

Slowing Down, Some Day…

While God and family are foremost in her life, Rivers knows that feeling good in her body matters to showing up strong: “When I think about the things that I need to do and be to bring my best self to every situation, I have to be physically fit.”

Moving to South Carolina after being a hardcore New Yorker, has enabled her to be in the water and on the golf course year-round while working very full weeks. She’s taken up synchronized swimming recently and performs in a 3-day show every February. She also loves to cook for her and her husband, and baking has become a new hobby. She bakes hundreds of cookies every holiday season for neighbors, friends and family. She says she does want to slow down, but soonish.

“I believe in living life to the fullest. There is no way I’m going to have any regrets when it’s my time to close my eyes for the final time. I will leave it all out here,” she muses. “When I look at all that I do in a given day or week, I recognize that it’s probably in the 95th percentile of what most people do every day or week. But I guess that’s just the New Yorker in me. I wake up every morning, give thanks, and press the ‘Go’ button on a fulfilled life.”

By Aimee Hansen

“Don’t be afraid to be authentically you,” says Tara Stafford, Project Manager, Operations & Innovation at PGIM. “If you can do that, you’ll be surprised how your contributions can positively impact the business, those around you – and beyond.”

“Don’t be afraid to be authentically you,” says Tara Stafford, Project Manager, Operations & Innovation at PGIM. “If you can do that, you’ll be surprised how your contributions can positively impact the business, those around you – and beyond.”