Before the word ‘intersectionality’ was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, bell hooks critiqued a narrowed feminism that hailed from the white middle class living room and neither addressed interlocking webs of oppression nor recognized its own race and class privileges – therefore, blindly disregarding the multidimensional plights of non-white, underprivileged women.

Before the word ‘intersectionality’ was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, bell hooks critiqued a narrowed feminism that hailed from the white middle class living room and neither addressed interlocking webs of oppression nor recognized its own race and class privileges – therefore, blindly disregarding the multidimensional plights of non-white, underprivileged women.

Her message has become undeniably resonant over the last two years – and not the least of all, her argument that humanity would need to brave the revolutionary path of deep self awareness and self actualization, as she taught, “once you learn to look at yourself critically, you look at everything around you with new eyes”.

A Revolutionary Feminism For Everyone

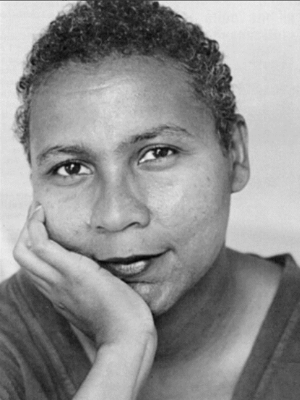

With her death on December 15th of last year, bell hooks, born as Gloria Jean Watkins in 1952, left behind a legacy, as well as over 40 books in 15 different languages, of challenging and championing feminism.

In her book Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism, she grounded her feminist approach in the struggles of black women. In Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, she proposed a revolutionary feminism: “Feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.”

Further, hooks wrote, “The foundation of a future feminist struggle must be solidly based on a recognition of the need to eradicate the underlying cultural basis and causes of sexism and other forms of group oppression. Without challenging and changing these philosophical structures, no feminist reforms will have a long-range impact.” Black feminist writer Barbara Smith wrote that anything less than a feminism that freed all women was “not feminism, but merely female self-aggrandizement”.

hooks also advocated that feminism was not men versus women, but all versus sexism, a conditioning both present in and oppressive to everyone. She wrote: “And that clarity helps us remember that all of us, female and male, have been socialized from birth on to accept sexist thought and action,” later continuing, “To end patriarchy (another way of naming the institutionalized sexism) we need to be clear that we are all participants in perpetuating sexism until we change our minds and hearts, until we let go of sexist thought and action and replace it with feminist thought and action.”

Emphasizing that oppression costs too much to everyone, including to those who overtly benefit from it, she called for ending sexism, racism, class elitism, and imperialism through not reform, but a revolution of self-actualization. She asserted any real movement of social justice to be based in the ethic of love, writing in her work Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, “The moment we choose to love we begin to move against domination, against oppression. The moment we choose to love we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others.”

And yet with her departure, we still stand in our half-awoken adolescence of realizing the necessity of self-development she spent her life advocating for.

A Workplace That Is Still Damagingly Exclusive

According to authors in Harvard Business Review, women of color are still culturally encouraged to be grateful for what they have, discouraged when declining undervalued work or seeking greater power and resources, and often fear backlash. Meanwhile, the angry black woman stereotype “not only characterizes Black women as more hostile, aggressive, overbearing, illogical, ill-tempered and bitter, but it may also be holding them back from realizing their full potential in the workplace — and shaping their work experiences overall.”

Whereas anger is a normal workplace emotion, when expressed by a black women particularly, it’s perceived (assumed) as a personality trait – rather than due to validating external circumstances, despite little substantiation for that perception. Meanwhile black women often find themselves stereotyped, kid-gloved or imposing tone policing on their own voices. Echoing hooks in regards to self-development, the researchers suggest an antidote to this is deeper self-reflection and empathy by those in the workforce.

Even well-intentioned leaders can put extra responsibilities and burdens on successful black women in the office. When black women are implicitly seen to speak as representative for a group, rather than for themselves, or when they are disproportionately committed to external opportunities as visible symbols of parading a company’s diversity, the pressure and time commitment can be overwhelming. Meanwhile, the stereotype of the strong black woman means managers are less likely to check in to see if they are doing okay with managing the workload. Couple that with it being societally instilled that black women will have to work twice as hard as others to succeed.

Not only this, but the perception gap creates a gaslighting of the workplace experience for black women – McKinsey notes that black employees are 23% less likely to see there is support to advance, 41% less likely to view the promotion process as fair and 39% less likely to feel the company’s DE&I program are effective, relative to white colleagues. Gallup found that black women are less likely to feel valued, treated fairly and respected in the workplace. Consistently, the experience of fairness and organizational commitment to addressing bias is lower for them, and they are also less likely to consider themselves as thriving.

When it comes to women of color and the multidimensional factors they face, the glass ceiling has been reframed as a concrete ceiling. Too often the corporate definition of leadership has proven to exclude women of color – with standards of what leadership looks still contingent upon traits most associated with white males.

If you question that, consider that a study has recently shown that black women are indeed penalized for natural hairstyles in an interview setting, as authors wrote: “Black women with natural hairstyles were perceived to be less professional, less competent, and less likely to be recommended for a job interview than Black women with straightened hairstyles and white women with either curly or straight hairstyles.”

The emotional tax black women are paying to be in workplaces rife with conscious and unconscious incidences of exclusion is not an abstract concept – it’s visible in functional MRI brain scans, which show that black women who have experienced more incidents of racism have greater response activity in the brain regions most associated with vigilance and anticipating incoming threats. This ultimately can have a trauma-like impact on health.

The researchers also state that “a disproportionately high amount of brain power may go into regulating, or inhibiting, their emotional responses to these situations” – which is consuming energy that could otherwise be put into well-being, thriving, creating and innovating.

Inclusion Does Rest Upon Collective Self-Development

So amidst the Great Resignation, black women are leaving the workforce in record numbers, with a track record of having outpaced all other women when it comes to daring the journey of entrepreneurship and achieving business growth within it.

With research indicating that “one of the fastest ways to accelerate change and effectively begin to address the racial wealth gap is to listen to and invest in Black women,” Goldman Sachs launched, in partnership with Black women-led organizations and others, the One Million Black Women initiative – committing $10 billion in investment capital and $100 million in philanthropic support to be focused on key moments, from early childhood to retirement, that offer the greatest possibility to narrow the opportunity gaps and positively impact lives.

Meanwhile, Gallup asserts that the exclusion experiences of black women in the workplace can be largely addressed by managers, as the crux of feeling engaged comes from coaching. Seeking to coach and sponsor those who are under-championed is where you begin – getting to know and support every person, in their individual strengths and challenges, is where engagement is created. Gallup suggests that to be inclusive, more workplaces need to train their managers to become coaches.

As summarized in the Journal of International Women’s Studies, hooks consistently advocated that only “the self-development of a people will shake up the cultural basis of group oppression.”

Haven’t the prominent themes of the last couple years – braving the difficult conversations, recognizing the unconscious biases in everyone, listening to the experiences of others, cultivating a personal growth mindset of being open to being wrong and learning – echoed the message of this visionary, who emphasized our interconnectedness and collective responsibility to expose the ideology of the status quo that exists in each of us?

As hooks wrote: “No level of individual self-actualization alone can sustain the marginalized and oppressed. We must be linked to collective struggle, to communities of resistance that move us outward, into the world.”

By Aimee Hansen